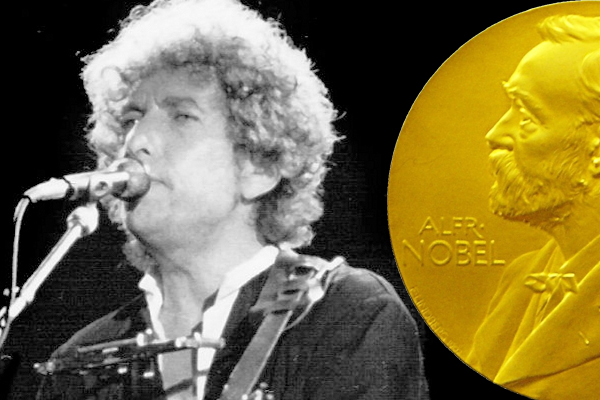

The Answer, My Friend, to Who Won the Nobel in Literature this year, is Blowin' in the Wind

The biggest news to hit the literary world within the last two weeks, as far as I'm concerned, has been the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan - and the reclusive singer's notable lack of response to winning the much heralded award. The decision to award Dylan with the prize was quite controversial. His lack of response to the award has also been controversial, with one member of the Committee calling him "arrogant," while writer Will Self urged him to reject it because of the prize's ties to an explosives and armaments fortune.

Personally, I find this unexpected and beautiful news. To recognize that literature doesn't have to be confined to the pages of a book breaks new ground and gives the nod to societies (such as Somalia) that have long relied on oral traditions to create and sustain culture and society. I also can't help but wonder (although this may be my American solipsism shining through) whether this is a nod to the racial injustices currently making headlines across the country, especially when you stop to consider Dylan's work. "How many ears must one man have/before he can hear people cry?/ And how many deaths will it take til he knows/ that too many people have died?" Something to consider.

Of course, it would have been cooler if Dylan hadn't snubbed the awards committee. But as I'm an avid Dylan fan (my children heard so many repetitions of "Blowin' in the Wind" during their infancies that they probably know the song by heart without even realizing it), I will give him the benefit of the doubt and suggest that he likely was quite surprised by the award, and probably had some deep thinking to do about his reaction to it.

Speaking of ground-breaking work...

Marvel Comics' latest hero? A mom of five living in Madaya, Syria. They've taken the true story of a woman who has been living with her young children in the besieged city for over a year and made it into a graphic novel/comic book format. I can't tell you how appreciative I am that I found this source, because I will be teaching an online version of Intro to Global Issues and World Affairs next semester and I love using offbeat formats. It's a remarkable story and really brings the reality of living in Syria into focus. By and large, the citizens of Syria are now caught within a maelstrom of horror and violence, in which foreigners have largely taken control of the rebellion, and Assad has the help of Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia as he relentlessly works to crush his own society - his own people! - out of existence. All in the name of victory. No one will win this war. But Marvel's "Madaya Mom" does offer us a different and meaningful way of framing and understanding the cataclysm that has engulfed Syria, and gives us the war's true hero: the Syrian family.

Navel Gazing with Jessica:

Maria Semple's new book, Today Will Be Different, is almost as absorbing, funny, and attractive as her previous novel (which, let's face it, was nearly perfect). But I am SO over the trend of writing with flashbacks. If I take the book apart and reorganize it to my satisfaction, will anyone report me to the reading police?

Now that I've been considering this idea of reorganizing the book, especially within the context of this particular story, it makes me wonder: would it still be the same book? Would I no longer be merely a reader, but something more substantial? Would it dissolve the already porous boundaries between artist and audience? Producer and consumer? Or is it no different, really, from reading for my own enjoyment and analysis? I can't stop thinking about this. Where does the artistry end and the reader begin? It's so much more difficult to discern those differences than it is most other art forms: ballet, cinema, theater. For a book to really come alive there needs to be a collaboration between author and reader. And the author has no say, beyond the work itself, as to whether and how the collaboration will occur. What shape does the final version of the narrative take? The final draft isn't what winds up in the reader's hands - it's what winds up in the reader's head. What an act of faith each author makes!

"Paris is a Moveable Feast": Shakespeare and Company Makes Literary Waves, Again

I have been a die-hard Sylvia Beach fan since I was in college, possibly because she was the first historical figure I "met" who struck a chord in me - another bibliophile! A kindred spirit! When I was attending high school and college in the early 1990s, women like Beach didn't often make the cut in literary or historical discussions, and so I clutched her tight. I was so proud to have stumbled onto her and her legendary bookshop, Shakespeare & Co. (1922-1941) all by myself whilst deeply immersed in the works and biographies of the "Lost Generation" and their modernist movement. An American, Beach opened a little bookshop in Paris as the Roaring Twenties began, and kept it going until forced to close during the Nazi occupation of France; although Hemingway reportedly "personally liberated" the shop in 1945, it never reopened with Beach at the helm. Her shop and her vibrant personality attracted perhaps the most star-studded list of bookworms in modern history: Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and so many more made Shakespeare & Co. their second home. When Joyce could not find a publisher for his ground-breaking masterpiece, Ulysses, Beach published it herself, in 1922, under the Shakespeare & Co. moniker - and helped change the face of modern literature. She also stocked banned books of all kinds, and allowed patrons to buy or borrow volumes.

|

| Sylvia Beach and Ernest Hemingway in front of Shakespeare and Company, circa 1928 |

In 1951, George Whitman opened his own bookshop on Paris's Left Bank, and after a few years he renamed it Shakespeare and Co. in honor of Beach; it's been open ever since. Whitman also named his daughter after Beach: Sylvia Beach Whitman took over Shakespeare and Co. in 2004 and continues to run the shop today. Why am I telling you all of this? Well, first, because Sylvia Beach rocks. Secondly, because the shop's motto: "Be Not Inhospitable to Strangers Lest They Be Angels in Disguise" is one we all could stand to remember in this day and age. And last but not least, because Beach and her shop have been back in the literary news of late with the publication of a new volume dedicated to the history of Shakespeare & Co! Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart dropped on September 26, and contains dozens of essays, poems, interviews, and illustrations that together reportedly create an extraordinary collage of the life and times of literary Paris over the last century. I can't wait to get my hands on it. If you don't have the money for a hardback, here's a little history of Beach and her shop. I also highly recommend Beach's memoir, Shakespeare and Company, and Noel Riley Fitch's beautiful work, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties, which has been close to my heart and next to my bed for the last 20 years.

That's all for now! I had hoped to offer you more this time, but then the Cubbies made it to the WORLD SERIES so I'll be jetting home to Chicago for some celebrating this week! #CubsNation